By Anand Venigalla

Staff Writer

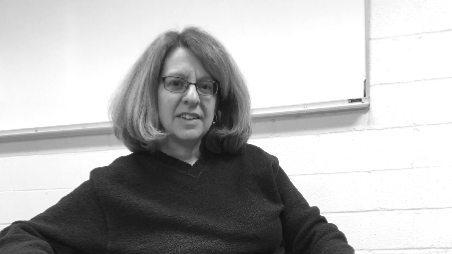

Students of all majors are required to take a certain number of core courses across a wide variety of disciplines to receive a well-rounded liberal arts education. Many students complete the 45 credits in their core requirements within their first two years before delving into the required and elective courses for their specific major. A committee of professors have been working this year on reducing the number of credits in the core curriculum from 45 credits to 32 or 33 credits. Professors John Lutz of the English department, Jay Diehl of the history department, and Amy Freedman of the political science department co-chaired the Thematic Core Curriculum committee.

Elaine Patrikis, a sophomore music education major, is enrolled in two core classes this year. “This semester I am taking a history course; it’s History 1 Western Civilizations. I’m taking Political Science 2 next semester,” she said. “They’re not very challenging, but it’s important that you continue your education even in a core class, even though you’re here to find something you’re gonna specialize in and become very good in.”

Vincent Torelli, a freshman radiology major, is enrolled in Post Foundations, ENG1, MTH3, HSC101, BIO103. Torelli is satisfied that he is getting a well-rounded education. “My English class is awesome, [Professor Hempel] is great,” he said.

The university administration is implementing a reduced core with a new thematic curriculum for fall 2018. The new core will consist of 12 or 13 less credits than the current core, which is the standard amount at most universities. The first-year experience will consist of 13 credits, Post 101, First-Year Seminar, Writing I, Writing II, & Quantitative Reasoning, and new thematic clusters will account for the remaining 19-20 credits. The clusters will offer classes in Scientific Inquiry and the Natural World (inquiry and analysis, quantitative reasoning); Creativity, Media and the Arts (creative capabilities, critical thinking); Perspectives on World Cultures (intercultural knowledge); Self, Society, and Ethics (ethical reasoning, critical thinking); Power, Institutions, and Structures (ethical reasoning, critical thinking).

The core faculty committee began meeting in May 2017 to design this new curriculum, according to Lutz, associate professor of English, and president of the Faculty Council. “We set out to create a 32- to 33-credit thematic core curriculum, and we’ve divided the core into a first-year experience and a second level, to be taken mainly in the sophomore and junior year, of thematic cluster,” Lutz said. “Those clusters will be populated with courses that correspond to the theme. One of the distinctions between what we have now and what we’ve created is that many of the core courses now are in a distribution model distributed among disciplines. So we’ve now completely broken out of individual disciplines and moved the core in an interdisciplinary direction by having categories that students will take classes in.”

Students will take courses from these five different categories, with greater choice in what they take. “Some of the courses will be the same,” Lutz said, “except instead of taking a science sequence, students will take a biology course in the Scientific Inquiry and the Natural World category, or students could take an art core class or a Shakespeare class or a creative writing class in [the Creativity, Media and the Arts cluster].”

This new core curriculum, according to Lutz, will entail a re-design of all the courses. The new design for the first year includes a development of the first-year seminar and Post 101, with new first-year seminars. “What we’ve done is create two different levels,” Lutz said. “A couple of things – it’s a reduction of the credits of the core. So this will give students more opportunity to take electives. We’re [also] creating at least twelve credits of electives and also giving students more room to include more minors in their degree.”

In addition, Lutz hopes that this new design will lead to more interdisciplinary work among faculty, development of learning communities, and intentional linkages between core courses and courses within students’ majors.

Freedman said that the new changes and thematic clusters will give students more choice in fulfilling their general education requirements. However, some faculty members have noted a potential downside in the new core curriculum. “The number of credits students will take in the core curriculum has shrunk,” she said. “So where current students and students in the last couple of years have had to take a larger number of core general ed requirements, they [the courses] had more depth. We’re trading the advantages of choice and exibility, but there’s a loss in depth.” Students won’t be taking a sequence of courses in this new system, unless they choose to do so as electives. They won’t be required to take, for example, two lab courses or two economic courses.

Freedman noted that the changes are “the way most universities have gone.” However, there is wide variation among colleges. Brown University, for instance, has a core curriculum with zero credits. Others, like Columbia University have a set core curriculum which requires completion of Literature Humanities, University Writing, and Frontiers of Science in the first year, Contemporary Civilization in their sophomore year, and Art Humanities and Music Humanities by the end of junior year.

Faculty members, Freedman said, will be able to create new courses and do interdisciplinary work. “If I wanted to team up with an English professor, I would teach political science through the use of novels, or if I want to team up with someone from economics [I could] do a political economy class.”

This should increase student enrollment in these classes, “which gives us a greater incentive” to create new interdisciplinary courses, Freedman said. “The advantage of this to faculty is really in opening the door and incentivizing people to do new and creative things.”

The new core is not entirely brand new. Freedman stressed that this new configuration was not “starting from scratch.” Some of the classes already existed and could either be changed or set into one of the clusters. “It’s a new way of thinking how the classes connect to each other.”

Advisors have already been telling students that the core curriculum would be changing, even before the nature of these changes was known.

Diehl served as a core committee member at large, in addition to sharing co-chairmanship with Lutz and Freedman. “My main role [was] to keep the focus on pedagogy, on learning, and on trying to create a core curriculum that is intellectually consistent and not just a product of convenience or logistics,” Diehl said.

The change in the core does not only affect the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, but faculty from other academic areas as well, Diehl said.

He noted that the first-year seminar, instead of being something that fulfilled other requirements, is its own self-contained requirement in this new program. “In the current core, you take a first-year seminar, say, History 7. In addition to meeting the requirement that you take a first-year seminar, it also fulfills one of your History requirements. In the new core, you take a first-year seminar and fulfill only the first-year seminar requirement, none of the other distribution requirements in the thematic categories (although it might fulfill a major requirement). Making the first-year seminar into its own requirement is a way of allowing students to delve into separate interests and also give flexibility to meeting the thematic requirements. For example, with quantitative reasoning, that is the product of the decision that it is a foundational skill that needs to be established as early as possible in the students’ college career.”

Be First to Comment