By Carlo Valladares

Staff Writer

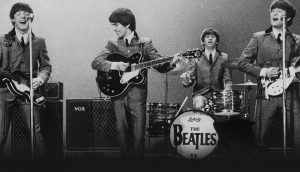

As hip-hop listener for over 10 years, I have become fascinated with the genre. The trends, the fashion, the subjects, the culture, and the changing focus of the emcees has kept me engaged in the genre for years, and will continue to do so into my adult life. I have always loved the genre for its lack of many instruments other than a turntable – or more recently, a computer and DJ production program. The fact that all you need is lyricism over electronic drums, hi-hats, crashes, and a sample makes the music very accessible for the creator, and that alone has kept me coming back.

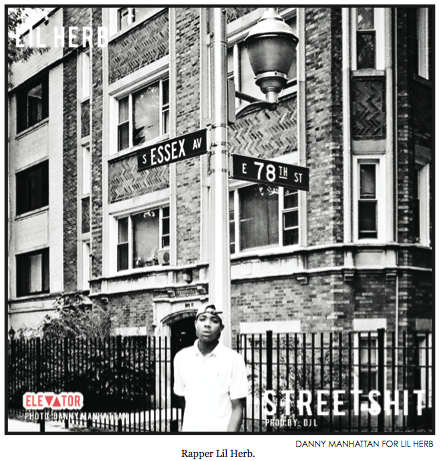

Although hip-hop started in 1977 in New York City, 37 years later the objective is still the same for Lil Herb: A young, 17-year-old burgeoning rapper from Chicago’s Eastside. On February 17, Lil Herb dropped his debut mixtape, “Welcome to Fazoland.” The mixtape is a dark themed view into the life of a kid from, what the FBI now calls, the murder capital of the United States, and growing up in 21st century Chicago gang culture. This millennial culture has since made its imprint on hip-hop history by creating “Drill Muzik,” a sub-genre of “Trap Music,” which is essentially a sub-genre of “gangster rap.”

The 20-year-old themes of gangsta rap still hold true for Drill: You express how you see the world, which is for many of these young individuals, a life of circumstantial violence and crime. Lil Herb certainly does create Drill music, a style of hip-hop that is distinct by its nihilistic flow delivery, dark-synths, skittering machine-gun like hi- hats, thundering 808s (slang for bass) and dead-souled party vibe. At its greatest points, the style is hard, cold, and never shows signs of remorse.

This could be interpreted quite literally; many of the genres most popular figures, like Chief Keef, Lil Durk, and Lil Reese,

have all been accused of or have committed acts of violence, even if they themselves aren’t directly involved. They are all well-documented gang members, and their peers have not received million dollar deals, so they are still on the south side committing crimes, which in turn affects the spotlight of their now celebrity friends.

However, Lil Herb is different in two areas: his gang affiliation and his unrelenting poetic skill, a skill that mirrors his east coast forefathers rather than his Drill contemporaries. When you hear Lil Herb, you immediately hear the sounds of New York City rappers from the 90s, like Jadakiss, Styles P, Camron, and Jay-Z, all which express hip-hop in the truest poetic manner. You listen to these rappers as if they were anthropological street speakers, for they have perfected their poetic craft, illustrating their lives and stories through rhythmic speech. Lil Herb can rap better than his Chicago peers, and that’s what is making his mix tape receive rave reviews from numerous music critics.

Lil Herb’s mix tape starts with samples of his verses from previous singles, prior to his 2014 debut, expressing to the listener that, yes, this may be his debut, but Herb is by no means a rookie. He’s been in the studio since 2011. Due to this new YouTube music culture, an artist does not necessarily need a label, MTV, or an album to push out videos or songs – an artist now has a platform to release singles on the Internet. The intro also illustrates his rapid-fire flow that hits you like a punch to the face: the type of flow that turned the lives of street kids into film adaptations, like 2009’s “Notorious.”

The standout song, “At The Light,” is a grim and tough track, produced by fellow Chicago native DJ L. A telling moment in the song is when Herb describes a traffic light as not only a safe way to facilitate the movement of cars, but a place where his enemies could easily catch him off guard and kill him. “Gotta look to my left and my right, I’ll be damned I get left (as in left for dead) at the light, summer time, I remember them nights.” When Herb talks of violence, it’s usually as a result of pain for a deceased friend and his back is against the wall. “Me and Kobe off ACT with the sprite, he just left us and they took his life, wish the lord would just let him fight, but don’t trip man it’s gon be aight, Cuz I got lil dudes tryna earn stripes, I could write them a check for your life, they might walk up and check you tonight.”

In the reflective track “Mamma I’m Sorry,” Herb reminisces on his past actions, the effect it has on his mother, and his plans for the future. “Definition of a woman, when our problems was taken over you brought us from under, as a youngin’ you always told me I won’t need for nothin’, I just never settled for less cause I can’t see you strugglin’, that’s why I got it on my own and I stayed away from home cause I ain’t want my sister growin’ up, watching me doing wrong.” Herb doesn’t stop there, he has plans for his mother’s well-being, “All I wanna do is move you and my grandma out the state put y’all in some nice estate, name on ya license plate so I grind like it’s my time, even if I die today.”

The entire mixtape is filled with lyricism over dark and cold beats. Herb comes off as a desperate rapper who’s out of options — that’s because he really is. His lyricism will be the source of his success, to better his undesired living and social conditions of his South Side Chicago neighborhood.

Be First to Comment