By Pete Barell

Arts & Entertainment Editor

“The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness” is a documentary film by Mami Sunada that chronicles the year leading up to the 2013 release of “The Wind Rises,” by the then 72-year-old Hayao Miyazaki (“Spirited Away’’) of the prolific animation group Studio Ghibli.

Sunada, a newcomer with only one other feature under her belt, shows an inside look into Miyazaki’s private life and world, as well as his relationships with his fellow filmmakers at Ghibli. Such filmmakers include director Isao Takahata, and producer Toshio Suzuki. The documentarian was given access to Ghibli during her visits, with often candid footage harvested over the course of the year. This is the first feature-length theatrical film about the studio, and premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September for its North American debut.

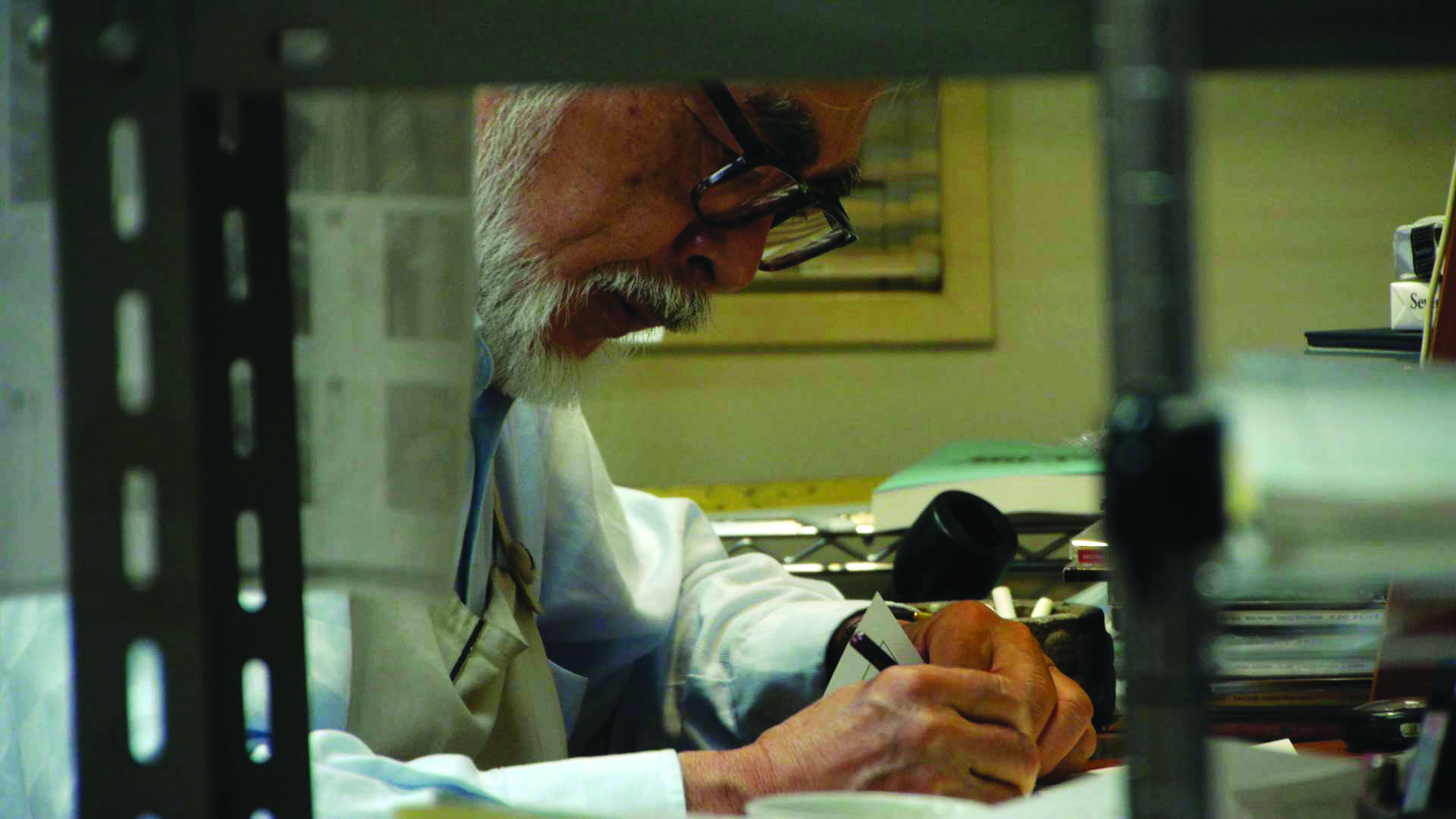

Studio Ghibli is portrayed in the film as a place of simultaneous work and play. Miyazaki is a perfectionist, and a pessimistic one at that; but his interactions with his fellow animators are filled with an underlying humor. He arrives at the studio every day at the same time, on the clock, and is almost always seen wearing a work apron. Early in the film, Miyazaki does his morning aerobics to music at work along with the majority of his team. Cut together with this imagery is a scene in which Suzuki discusses merchandizing and his work as producer—the business side of the studio parallels light-heartedness. Sunada’s choice of editing is wisely done, quickly establishing a calming tone and wholeness to the viewer.

“The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness” often feels like a narrative story, driven by the poetic language, observations, and banter of the Ghibli workers as they face new challenges during the making of “The Wind Rises”—the film Miyazaki states will be his last feature, and one that is deeply personal; Miyazaki is often caught ruminating on the state of the artistic world while smoking a cigarette, his casual words dusted in an odd melancholy that is thought provoking. He is caught speaking about family, his philosophical views, and his own films in a raw way.

Takahata is briefly seen in the film, taking a role in the background as he works on his own film, “The Tale of the Princess Kaguya,” at a different Ghibli location. The filmmaker, who was once a key mentor to Miyazaki early in their careers, is portrayed as a secretive man on the verge of retirement, having not made a feature film in more than a decade. The focus of this documentary is Miyazaki, but the somewhat strained relationship between the two filmmakers within Studio Ghibli is given special attention that implies a deep respect, and also a distance.

Sunada does not lay out the studio’s history in a linear, dull fashion, but instead delves into it when a modern problem has been similarly seen in the past. At these times, she uses choice archive footage of the filmmakers, allowing smoother access into the documented story. Shots of Japanese nature push the film along in a meditative way, reminiscent of the signature peaceful pauses and breaks in scenes found in Miyazaki’s work. This silence is key to the minimalistic tone of the documentary.

Miyazaki and the studio are contextualized in a worldly manner, with references to the 2008 Economic Recession, the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, and politics discussed freely. This touching base with current events creates a further feeling of realism within the documentary, humanizing the studio and its employees as not only workers, but as members of an imperfect society.

Just as silence is key to this documentary, so is the music. Masakatsu Takagi supplies a piano-heavy score reminiscent of the whimsical work of Ghibli composer Joe Hisaishi, adding to the strong tonal ties this film has with the narrative films of the studio. There is this feeling that Sunada has taken cues from her subjects, and incorporated their minimalistic, yet illustrative styles into the documentary medium.

“The Kingdom of Madness” is not just a melancholic treat for Ghibli fans, but a fine study of the creative world and a master class in story-driven documentary filmmaking. The documentary released on Nov. 28 at the IFC Center in New York City.

Be First to Comment